Essay

Native art, culture, education and healing in Hawaiʻi: Family stories of connection

Drew Kahuʻāina Broderick, Maile Meyer, Dr Manulani Aluli Meyer and Meleanna Aluli Meyer

Participants in the opening ceremony of ‘KE AO LAMA, Enlightened World’, prior to entering ‘Nā Akua Ākea, The Vast and Numerous Deities’, one of five interconnected exhibitions presented by the Hawai‘i State Foundation on Culture and the Arts as part of the 13th Festival of Pacific Arts and Culture, Capitol Modern, Honolulu, Kona, Oʻahu, 7 June 2024 / Photograph: Drew Kahuʻāina Broderick (DKB)

Participants in the opening ceremony of ‘KE AO LAMA, Enlightened World’, prior to entering ‘Nā Akua Ākea, The Vast and Numerous Deities’, one of five interconnected exhibitions presented by the Hawai‘i State Foundation on Culture and the Arts as part of the 13th Festival of Pacific Arts and Culture, Capitol Modern, Honolulu, Kona, Oʻahu, 7 June 2024 / Photograph: Drew Kahuʻāina Broderick (DKB)‘Hoʻoulu Lāhui: Regenerating Oceania’, the 13th Festival of Pacific Arts and Culture was convened on the island of Oʻahu, in United States-occupied Hawaiʻi, 6–16 June 2024.1 It has been over 50 years since the South Pacific Commission organised the inaugural festival in Suva, Fiji, and a century and a half since David Kalākaua, elected king of Ke Aupuni Hawaiʻi (the Hawaiian Kingdom), shared his famed motto with the world — ‘E Hoʻoulu Lāhui’, which translates as ‘to grow or nurture a nation or people’, specifically, of course, the Hawaiian nation and its people.2 At that time, in 1874, after nearly 100 years of unfathomable loss — mass death due to introduced infectious diseases, the forceful removal of cultural practices by Protestant missionaries, and widespread dispossession due to demands for the privatisation of land by American businesses — the Native Hawaiian population had collapsed from an estimated 1 million in the late eighteenth century to less than 50,000 in the late nineteenth century.3 King Kalākaua, like the South Pacific Commission, understood that if ‘we’ — Native Hawaiians and Indigenous peoples of the Pacific, more broadly — are to survive and maintain some semblance of independence in the face of colonisation and ongoing occupation, it is absolutely necessary to grow our national consciousness by invigorating our people and advancing our cultural practices.

* * *

It is now mid July 2024, and many at this time are still reflecting on the significance of the 13th Festival of Pacific Arts and Culture, a transoceanic exchange that brought together thousands of delegates and visitors from more than 20 Pacific Island nations for a brief, but memorable, celebration. Taking our cues from the festival, we know we must continue to rekindle and repair our relationships with one another as part of a larger effort to perpetuate diverse and creative cultural practices across Oceania. The event reminded us of the ways in which Indigenous internationalism and solidarity influence the health and wellbeing of Moananuiākea (or Moananui, encompassing the Great Ocean region known as the Pacific), together with the caring social bonds of our immediate families (both chosen and given) that sustain generations and communities.

An installation view of ‘ʻAi ā manō’, curated by Kānaka ʻŌiwi artists Drew Kahuʻāina Broderick, Kapulani Landgraf and Kaili Chun as part of ‘KE AO LAMA, Enlightened World’, Capitol Modern, Honolulu, Kona, Oʻahu, September 2024, with (l–r) Scott Fitzel’s (Kanaka ʻŌiwi) Evolution – 7’0 Lei O Mano 2016; Kapulani Landgraf’s Māmakakaua 2021; ʻĪmaikalani Kalāhele’s (Kanaka ʻŌiwi) Divided 2018; and Sean Kekamakupaʻaikapono Kaʻonohiokalani Lee Loy Browne’s (Kanaka ʻŌiwi) Kalamakū (Guiding Light) 2004 / Collection: Art in Public Places Collection, Hawaiʻi State Foundation on Culture and the Arts / © The artists / Photograph: DKB

An installation view of ‘ʻAi ā manō’, curated by Kānaka ʻŌiwi artists Drew Kahuʻāina Broderick, Kapulani Landgraf and Kaili Chun as part of ‘KE AO LAMA, Enlightened World’, Capitol Modern, Honolulu, Kona, Oʻahu, September 2024, with (l–r) Scott Fitzel’s (Kanaka ʻŌiwi) Evolution – 7’0 Lei O Mano 2016; Kapulani Landgraf’s Māmakakaua 2021; ʻĪmaikalani Kalāhele’s (Kanaka ʻŌiwi) Divided 2018; and Sean Kekamakupaʻaikapono Kaʻonohiokalani Lee Loy Browne’s (Kanaka ʻŌiwi) Kalamakū (Guiding Light) 2004 / Collection: Art in Public Places Collection, Hawaiʻi State Foundation on Culture and the Arts / © The artists / Photograph: DKB An installation view of ‘ʻAi ā manō’, curated by Drew Kahuʻāina Broderick, Kapulani Landgraf and Kaili Chun as part of ‘KE AO LAMA, Enlightened World’, with (l-r) Abigail Romanchak’s (Kanaka ʻŌiwi) Kāhea, ‘a call’ 2019; Dalani Tanahy’s (Kanaka ʻŌiwi) Four Rivers, Four Trees 2016; Bob Freitas’s (Kanaka ʻŌiwi) That which is within must never be forgotten 1994; Kahi Ching’s Nānā I Ke Kumu (Look to the Source) Series 1 and 2 2022; Solomon Robert Nui Enos’s Future Kiʻi 2022 and Kapulani Landgraf’s Māmakakaua 2021 / Collection: Art in Public Places Collection, Hawaiʻi State Foundation on Culture and the Arts / © The artists / Photograph: DKB

An installation view of ‘ʻAi ā manō’, curated by Drew Kahuʻāina Broderick, Kapulani Landgraf and Kaili Chun as part of ‘KE AO LAMA, Enlightened World’, with (l-r) Abigail Romanchak’s (Kanaka ʻŌiwi) Kāhea, ‘a call’ 2019; Dalani Tanahy’s (Kanaka ʻŌiwi) Four Rivers, Four Trees 2016; Bob Freitas’s (Kanaka ʻŌiwi) That which is within must never be forgotten 1994; Kahi Ching’s Nānā I Ke Kumu (Look to the Source) Series 1 and 2 2022; Solomon Robert Nui Enos’s Future Kiʻi 2022 and Kapulani Landgraf’s Māmakakaua 2021 / Collection: Art in Public Places Collection, Hawaiʻi State Foundation on Culture and the Arts / © The artists / Photograph: DKBCommunity advocate and entrepreneur Maile Meyer (Kanaka ʻŌiwi) attests to the importance of nurturing culture through family:

My mother, Emma Akana Aluli Meyer, believed that children should be exposed to every possible kind of art form at a very early age. She did everything she could to foster an environment of unfettered access to creativity in all its expressions. Singing, dancing, life drawing, ceramics, cooking, weaving, lei making — you name it, we did it. This kind of upbringing liberated me and my siblings, and a lot of the neighbourhood kids, from believing that there was only one way to do or be in the world. Even though she lost her mother at an early age and was raised by Catholic nuns, my mother was always an independent, creative thinker [who valued] community presence and participation.

As I write this paper, my mother Maile Meyer, sister Emma, and aunties Meleanna and Manulani (Kānaka ʻŌiwi) — along with an extended support network of members of the not-for-profit arts and cultural organisation Puʻuhonua Society — are preparing to take part in activations commemorating Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea (Sovereignty Restoration Day).4 Established on 31 July 1843 by King Kamehameha ʻEkolu, Kauikeaouli, the national holiday of the Hawaiian Kingdom marks the end of temporary occupation by rogue agents of the British Crown, and the return of sovereign control to King Kamehameha ʻEkolu by Admiral Richard Darton Thomas, who travelled to Hawaiʻi on behalf of Queen Victoria to correct the ‘unwarranted transgression against the Hawaiian Kingdom’.5 Today, Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea is observed at Thomas Square Park, in Honolulu, where 181 years ago, the British flag was ceremoniously lowered and the Hae Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian flag) triumphantly raised to symbolise the restoration of the Hawaiian Kingdom — ‘Ua mau ke ea o ka ʻāina i ka pono’ (‘The life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness’).6

At ‘Hōʻeu Mana: Reawakening Ancestral Stories’, with (l–r) Keliʻi ‘Skippy’ Ioane Jr. (Kanaka ʻŌiwi), ʻĪmaikalani Kalāhele, Peter Kealoha (Kanaka ʻŌiwi) and Lei Niheu (Kanaka ʻŌiwi), pictured inside Tūtū’s Hale (Tūtū’s House), hosted by Hoʻoulu ʻĀina, organised by Puʻuhonua Society as part of Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea at Thomas Square, Honolulu, Kona, Oʻahu, July 2024 / Photograph: Kaʻōhua Lucas

At ‘Hōʻeu Mana: Reawakening Ancestral Stories’, with (l–r) Keliʻi ‘Skippy’ Ioane Jr. (Kanaka ʻŌiwi), ʻĪmaikalani Kalāhele, Peter Kealoha (Kanaka ʻŌiwi) and Lei Niheu (Kanaka ʻŌiwi), pictured inside Tūtū’s Hale (Tūtū’s House), hosted by Hoʻoulu ʻĀina, organised by Puʻuhonua Society as part of Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea at Thomas Square, Honolulu, Kona, Oʻahu, July 2024 / Photograph: Kaʻōhua LucasTo celebrate Lā Hoʻihoʻi Ea in 2024, Puʻuhonua Society collaboratively organised ‘Hōʻeu Mana: Reawakening Ancestral Stories’, a two-day community art gathering focused on ea, a Hawaiian concept encompassing sovereignty, life, breath and freedom. Through ‘Hōʻeu Mana’, photographers, sculptors, weavers, poets, musicians, dancers, farmers, chefs, filmmakers, activists, archivists, historians and storytellers — both Hawaiian and non-Hawaiian — held ground at Thomas Square Park to practise their freedoms. Participants, in the astute words of Hawaiian patriot Dr Kekuni Blaisdell (Kanaka ʻŌiwi), ‘recognize[d] what the British did and what the United States government has not done as of yet’.7

Educator and philosopher Manulani Aluli Meyer emphasises the roles that unity, family, difference and conflict play in diverse artistic endeavours:

Unity differentiates; we are the same, but different. If you are not mentored by difference, you are going to inevitably want to colonise it. I’ve learned to appreciate and honour our differences. So we’ve got to go where the conflict is greatest because, as [Brazilian philosopher] Paulo Freire says, ‘Conflict is the midwife of consciousness’. And that’s what family is to me — perceived conflict. Even in conflict, we must remain committed to recognizing the efficacy of, and the need for, the vibrational energy of loving and what loving can do for this planet. As artists heal and get to the next level, their ideas will inspire our evolution, not deconstruct it over and over again. So please, unless you’re in a moment of expansion and healing, don’t make me go see your art!

Counter to current trends in Western museums and educational institutions — namely, superficial, settler colonial and capitalist desires for indigeneity — community art events like ‘Hōʻeu Mana’, led by Native Hawaiian women and queer folk, and their allies, represent ongoing group processes committed to cultivating long-term structural and systemic change. In Hawaiʻi nei (this beloved Hawaiʻi), these do-it-yourself efforts can be traced back to the late 1960s and early 1970s, a particularly transformative time characterised by an archipelago-wide cultural and political reawakening. Energised by the possibilities of ea (sovereignty, life, breath, freedom), Native Hawaiian contemporary artists, educators and activists have been doing our thing — creating, educating, organising, protesting and protecting — for over half a century now.8

Carrying on the conscious work of previous generations, I began organising, curating, designing, advocating for and writing about the contemporary art of Hawaiʻi in the early 2010s. At the time, there were few engaged in this work from the position of a Native Hawaiian artist who was born and raised, as well as living and working, on Oʻahu. This was an important tactic to advance my own creative practice, and those of my family and friends, and our overlapping communities. By honing our skills, demonstrating our capacity and affirming our presence, the exclusionary practices and environments of museums and educational institutions — such as the Honolulu Museum of Art; the Department of Art and Art History, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa; and Hawaiʻi State Foundation on Culture and the Arts — would eventually be forced to acknowledge our significant contributions to the art ecosystem of Hawaiʻi. The thinking was simple: If they weren’t going to support us, then we needed to support ourselves — or as my family often says, ‘If there is work to be done, don’t wait for someone else to do it!’

An installation view of Bernice Akamine’s Ku‘u One Hānau 1999–2019, in ‘CONTACT 3017: HAWAIʻI IN A THOUSAND YEARS’, curated by PARADISE COVE (Drew Kahuʻāina Broderick, Bradley Capello and Marika Emi), and presented by Puʻuhonua Society at the Honolulu Museum of Art School, Kona, Oʻahu, 2017 / © Bernice Akamine / Photograph: Shuzo Uemoto/Honolulu Museum of Art School

An installation view of Bernice Akamine’s Ku‘u One Hānau 1999–2019, in ‘CONTACT 3017: HAWAIʻI IN A THOUSAND YEARS’, curated by PARADISE COVE (Drew Kahuʻāina Broderick, Bradley Capello and Marika Emi), and presented by Puʻuhonua Society at the Honolulu Museum of Art School, Kona, Oʻahu, 2017 / © Bernice Akamine / Photograph: Shuzo Uemoto/Honolulu Museum of Art School The procession from ʻIolani Palace to Aliʻiōlani Hale, featuring Bernice Akamine’s Kalo 2015–19, included in ‘Honolulu Biennial 2019: To Make Wrong / Right / Now’, curated by Nina Tonga (Tongan people), Honolulu, Kona, Oʻahu 2019 / Photograph: Teri Skillman / Image courtesy: Hawaiʻi Contemporary, Honolulu

The procession from ʻIolani Palace to Aliʻiōlani Hale, featuring Bernice Akamine’s Kalo 2015–19, included in ‘Honolulu Biennial 2019: To Make Wrong / Right / Now’, curated by Nina Tonga (Tongan people), Honolulu, Kona, Oʻahu 2019 / Photograph: Teri Skillman / Image courtesy: Hawaiʻi Contemporary, HonoluluArtist and filmmaker Meleanna Aluli Meyer reflects on the importance of creativity born of community and healing:

When I started on this journey as a creative, nearly 50 years ago, there was so little appreciation of and support for Native Hawaiians, let alone us Native Hawaiian contemporary artists. It was a sorrowful time. At a certain point, I just got tired of holding protest signs at marches and rallies. So instead, I began painting community murals to work through generational trauma and help envision abundant futures for Hawaiʻi. Understanding what it is to heal is a lifelong process and that’s how I found my way to the creative work I’m doing today. Art, education and cultural practice activated through community become tools for our own healing.

Exhibitions, essays, publications, films, screenings, lectures, workshops, panel discussions, community gatherings — no matter what the collaboration, the teachings of my mother Maile, Aunty Manu and Aunty Mele permeate it all. Through the actions of these Native Hawaiian women leaders and others like them, I have come to know our family’s stories of art, culture, education and healing. And through these intersecting stories, I am continuously arriving at a larger context for contemporary art and community in Hawaiʻi — a context that weaves together different places, peoples, practices and perspectives, all grounded in lived experience and guided by the multigenerational and grassroots efforts of many. By knowing and sharing these stories, I uplift those who embody Native Hawaiian values, participate in larger networks of solidarity, and believe in the power of creativity to accelerate processes of positive change in communities and institutions.

An installation view of ‘PEWA II’, curated by Drew Kahuʻāina Broderick, at SPF Projects, Kakaʻako, Kona, Oʻahu, May 2014, featuring Carl FK Pao's (Kanaka ʻŌiwi) (l-r) HE MAU ULEHOU 2005–14, RUB THE ULE ON THE KIʻI 2014, KU KA ULE, HEʻE KA LAHO 2014, KIʻI KUPUNA: MAKA 2013 and E HIOLO ANA NA KAPU KAHIKO 2014 / Courtesy: The artist / Photograph: DKB

An installation view of ‘PEWA II’, curated by Drew Kahuʻāina Broderick, at SPF Projects, Kakaʻako, Kona, Oʻahu, May 2014, featuring Carl FK Pao's (Kanaka ʻŌiwi) (l-r) HE MAU ULEHOU 2005–14, RUB THE ULE ON THE KIʻI 2014, KU KA ULE, HEʻE KA LAHO 2014, KIʻI KUPUNA: MAKA 2013 and E HIOLO ANA NA KAPU KAHIKO 2014 / Courtesy: The artist / Photograph: DKB An installation view of ‘He Noho Pili Kua He Noho Pili Alo’, at Aupuni Space, Kakaʻako, Kona, Oʻahu, October 2020, featuring (floor, l-r) Kānaka ʻŌiwi artists Auliʻi Mitchell’s Māwi, Wewehi, Lono-i-ka-nane, Kauapuakea and Wahinemuʻumuʻu, all 2020; and (walls, l-r) JD Nālamakūikapō Ahsing’s He Ahupuaʻa and Hoʻi I Ka Iwikuamoʻo, both 2019 / Courtesy: The artists / Photograph: Donnie Cervantes/Aupuni Space

An installation view of ‘He Noho Pili Kua He Noho Pili Alo’, at Aupuni Space, Kakaʻako, Kona, Oʻahu, October 2020, featuring (floor, l-r) Kānaka ʻŌiwi artists Auliʻi Mitchell’s Māwi, Wewehi, Lono-i-ka-nane, Kauapuakea and Wahinemuʻumuʻu, all 2020; and (walls, l-r) JD Nālamakūikapō Ahsing’s He Ahupuaʻa and Hoʻi I Ka Iwikuamoʻo, both 2019 / Courtesy: The artists / Photograph: Donnie Cervantes/Aupuni SpaceAccording to Manulani Aluli Meyer, it is all about changing an entrenched and somewhat misguided perspective:

‘NEPOTISM ROCKS’! Let’s make a bumper sticker! I tell people all the time: ‘I want to hire my sister. She’s three times better and twice as cheap’. And they usually respond, ‘You can’t do that. It’s a conflict of interest’. So whenever I can, I try to help organisations and institutions change their conflict-of-interest disclosures to statements of relationality. We can’t let the inauthentic voice be raised up as authentic. We need to challenge Westernised notions of integrity and insist on Native Hawaiian practices. I’d take a deep relationship over a community of strangers any day.

During my early teens, I would hang out after school at Native Books, an independent bookstore, art gallery and community venue dedicated to Hawaiʻi and the Great Ocean. At the time, Native Books was located up the hill from Niuhelewai Spring, on the corner of School and Aupuni Streets, in Pālama, a short walk from the Kamehameha Schools Bus Terminal, past Maluhia Cemetery, Jean Charlot’s vibrant United Public Workers Mural 1970–75 and Golden City Restaurant. My mom established Native Books in 1990, after a stint as the marketing director at Bishop Museum Press during the late 1980s. In 1993, she co-founded ʻAi Pōhaku Press, with her lifelong friend, book designer Barbara Pope (kamaʻāina) of Maunawili.9 Nā Mea Hawaiʻi, a resource centre and retail environment focused on the circulation of cultural materials and products, would follow several years later in 1996.

Maile Meyer recalls the community-based origins of Native Books:

My sister Manu invited me to the Native Hawaiian Leadership Development Conference she organised with David Kekaulike Sing of Nā Pua Noʻeau, through the University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo. My second child, Emma, was an infant, so I brought her along with me and a kupuna [community elder] offered to hold her. As I spoke to educators and took book orders, I watched Emma being loved and cared for, passed from person to person around the room until she returned to me. For the first couple of years before we opened the bookstore in Pālama, we sold books only through community events. I’d set up tables at craft fairs, swap meets, farmers markets, concerts and conferences, six to eight times a week. Back then, I was constantly asked why I sold books — since Hawaiians couldn’t read! That’s when I started to remind anyone who asked me that question, that the Hawaiian Kingdom had one of the highest literacy rates in the world.

An installation view of Reading Room 2022 by ʻAi Pōhaku Press (Maile Meyer and Barbara Pope) with KEANAHALA, in ‘Hawaiʻi Triennial 2022: Pacific Century – E Hoʻomau no Moananuiākea’, curated by Melissa Chiu, Miwako Tezuka and Drew Kahuʻāina Broderick, Capitol Modern, Honolulu, Kona, Oʻahu, February 2022 / Courtesy: The artists and Hawaiʻi Contemporary / Photograph: Christopher Rohrer

An installation view of Reading Room 2022 by ʻAi Pōhaku Press (Maile Meyer and Barbara Pope) with KEANAHALA, in ‘Hawaiʻi Triennial 2022: Pacific Century – E Hoʻomau no Moananuiākea’, curated by Melissa Chiu, Miwako Tezuka and Drew Kahuʻāina Broderick, Capitol Modern, Honolulu, Kona, Oʻahu, February 2022 / Courtesy: The artists and Hawaiʻi Contemporary / Photograph: Christopher Rohrer ʻĪmaikalani Kalāhele’s undated paracord and wire sculptures (l-r) Hānau Kane, ʻEle ʻEle Kane, Nā Mea Kane (Collection: Art in Public Places Collection, Hawaiʻi State Foundation on Culture and the Arts / © ʻĪmaikalani Kalāhele), in ‘Mai hoʻohuli i ka lima i luna’, curated by Drew Kahuʻāina Broderick, Kapulani Landgraf and Kaili Chun, Capitol Modern, Honolulu, Kona, Oʻahu, July 2020 / Photograph: DKB

ʻĪmaikalani Kalāhele’s undated paracord and wire sculptures (l-r) Hānau Kane, ʻEle ʻEle Kane, Nā Mea Kane (Collection: Art in Public Places Collection, Hawaiʻi State Foundation on Culture and the Arts / © ʻĪmaikalani Kalāhele), in ‘Mai hoʻohuli i ka lima i luna’, curated by Drew Kahuʻāina Broderick, Kapulani Landgraf and Kaili Chun, Capitol Modern, Honolulu, Kona, Oʻahu, July 2020 / Photograph: DKBA populist at heart, my mom established Native Books, co-founded ʻAi Pōhaku Press and opened Nā Mea Hawaiʻi in the hopes of reclaiming agency, and supporting knowledge exchange for and by the people — not to make a profit and certainly not, in social media jargon, for ‘likes’. True to form, throughout the 1990s, she would frequently distribute, for free or at cost, photocopies of the Kūʻē Anti-Annexation Petitions (1897) and Indices of Awards made by the Board of Commissioners to Quiet Land Titles in the Hawaiian Islands (1929). I didn’t know it then, but Native Books and Nā Mea Hawaiʻi’s eccentric scene — enlivened by Native Hawaiian artists, designers, poets, musicians, educators and community activists, such as Nakeʻu Awai (Kanaka ʻŌiwi), ʻĪmaikalani Kalāhele (Kanaka ʻŌiwi) and Calvin Hoe (Kanaka ʻŌiwi) — would have a tremendous influence on me in the decades to follow.

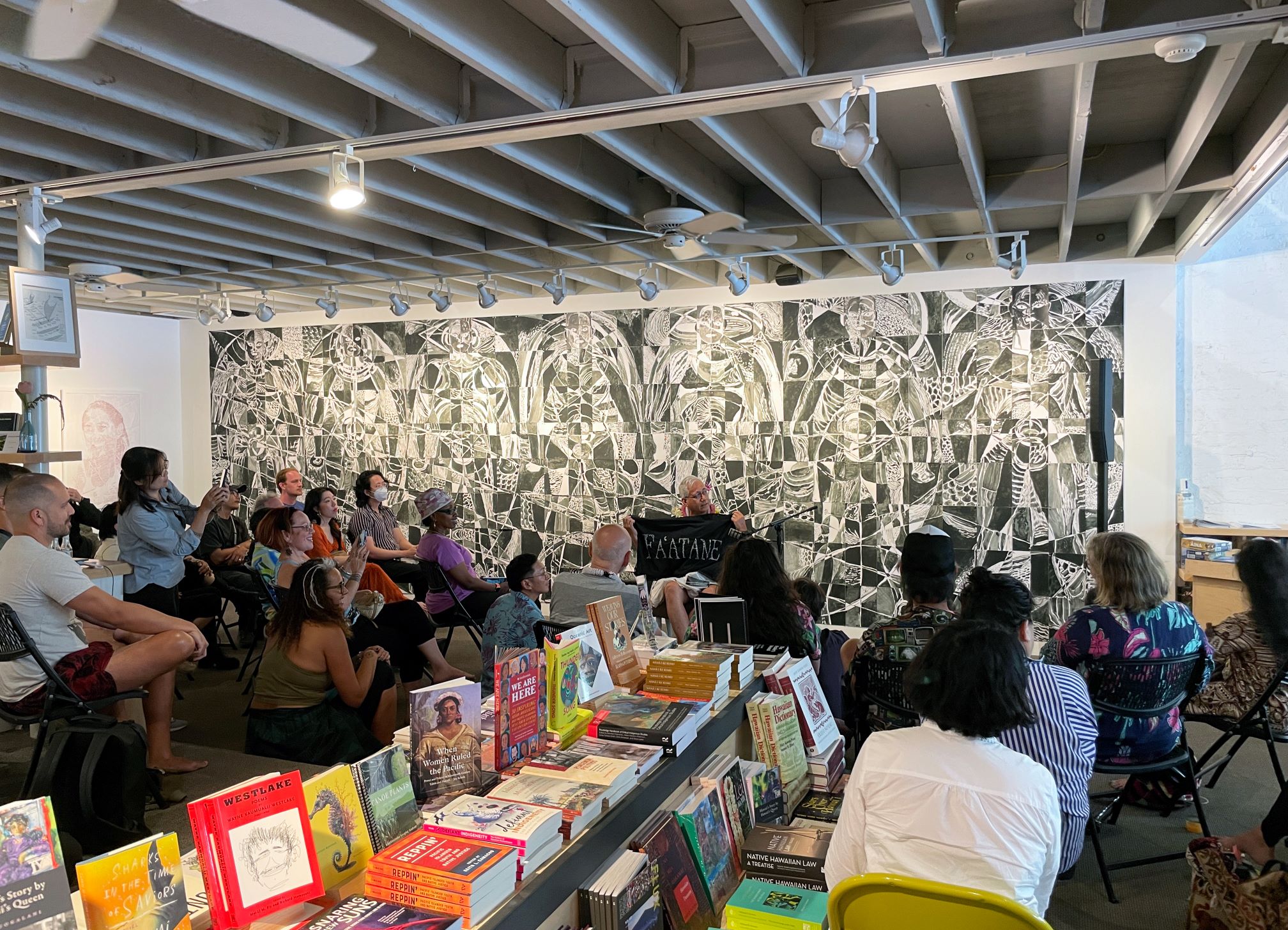

Faʻafafine artist and writer Dan Taulapapa McMullin (Tagata Sāmoa), originally from Sāmoa i Sasaʻe (known as the US ‘territory’ Eastern Samoa), who now lives in the Mahhicannituck (Hudson River Valley), celebrated the second edition of their artist book The Healer’s Wound: A Queer Theirstory of Polynesia (2022) at an event held amid the excitement and exhaustion of the 13th Festival of Pacific Arts and Culture.10 During the event at Native Books, I found myself thinking about a story Dan told a few years earlier at a poetry reading organised in parallel to the ‘Hawaiʻi Triennial 2022: Pacific Century — E Hoʻomau no Moananuiākea’. The story was about a young man who was playing an ipu (gourd) as part of a kanikapila (impromptu jam session), with Uncle ʻĪmai and Uncle Cal, at a gathering Dan attended decades earlier when Native Books was still located in Pālama. As Dan recalled, ‘I still remember how he held that gourd. How he played it, how beautiful it was . . . How I wished I was that gourd and he was playing me.’

Listening intently from the back of the room, with a big grin on my face, I was reminded of how influential puʻuhonua (places and people of refuge, peace and safety) like Native Books can be for those who don’t conform to the norms of a heteropatriarchal, settler colonial capitalist society. For 35 years, Native Books has offered space to gather, share and perpetuate culture, not just for Native Hawaiians and Hawaiʻi locals, but for anyone who is called to the venue from near and distant shores.

A view of a book launch and poetry reading for the second edition of Dan Taulapapa McMullin’s The Healer’s Wound: A Queer Theirstory of Polynesia (Native Books, Nuʻuanu, Kona, Oʻahu, 17 October 2024), with the painting Papa Heʻe Nalu i ka Wā Akua - Surfing in the Time of the Gods 2022 by Solomon Robert Nui Enos, in ‘Heʻe Nalu: The Art and Legacy of Hawaiian Surfing’, curated by Kanaka ʻŌiwi and Mescalero Apache artists Carolyn Melenani Kualiʻi and Ian Kualiʻi, first exhibited in ‘Heʻe Nalu: The Art and Legacy of Hawaiian Surfing’, curated by Carolyn Melenani Kualiʻi and Velma Kee Craig (Diné) for Heard Museum, Phoenix, Arizona, United States, 2023 / Courtesy: The artist / Photograph: DKB

A view of a book launch and poetry reading for the second edition of Dan Taulapapa McMullin’s The Healer’s Wound: A Queer Theirstory of Polynesia (Native Books, Nuʻuanu, Kona, Oʻahu, 17 October 2024), with the painting Papa Heʻe Nalu i ka Wā Akua - Surfing in the Time of the Gods 2022 by Solomon Robert Nui Enos, in ‘Heʻe Nalu: The Art and Legacy of Hawaiian Surfing’, curated by Kanaka ʻŌiwi and Mescalero Apache artists Carolyn Melenani Kualiʻi and Ian Kualiʻi, first exhibited in ‘Heʻe Nalu: The Art and Legacy of Hawaiian Surfing’, curated by Carolyn Melenani Kualiʻi and Velma Kee Craig (Diné) for Heard Museum, Phoenix, Arizona, United States, 2023 / Courtesy: The artist / Photograph: DKBAccording to Maile Meyer, spaces such as these are beacons in the dark:

After decades of community initiatives, we are now beginning to experience the full potential of what we’ve been planting together and sustaining through long-term relationships with one another. When I think of pilina — the importance of community and connection — I imagine a gathering in darkness, old Hawaiian-style with kukui torches. As lights are lit, filling the gaps of darkness, enough illumination brings awareness of those already waiting. With shared presence and purpose, many things are possible. The work never happens alone, even when we think we are out there on our own. We do it for our descendants, for all those future ancestors, so that they will know less heaviness and more joy!

During summer, in my pre-teens, I would visit Aunty Manu on Moku o Keawe, the Big Island of Hawaiʻi. At the time, she was an Associate Professor in the Education Department at the University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo, living and working, occasionally off-grid, at the intersections of Indigenous epistemologies, cultural and environmental stewardship, food sovereignty, transformational education and community healing. Aunty Manu often took me with her to visit muliwai, places where stream mouths embrace ocean tides, where fresh and salt water mix — Pāpaʻikou, Onomea, Kahaliʻi, Awawaloa, and so on, along the Hilo Palikū shoreline of the Island of Hawaiʻi. Here, surrounded by elemental forces, she would sit, sometimes for hours, listening, observing, gathering, making. Moving in stillness, she would shape waterworn basalt into ʻulu maika (disks) and pōpō pōhaku (spheres). Back then, I was too young to appreciate the knowledge that was being transmitted — from place to person, and from aunty to nephew. It wasn’t until my early twenties, when I was living abroad, that I would come to fully acknowledge these moments of water and stone.

Manulani Aluli Meyer has reflected on the significance of process and being present:

Repeating something enough, so that you’re not analysing it, so that you get out of your thinking mind, is to experience it fully. When I shape pōpō pōhaku [spheres], one hand is consistent, steady and moving in one direction, while the other hand is chaotic, random and moving without order. You need both — randomness and consistency — so there is a constant and a variable, and you have to trust in the process. Sustained repetition combined with sustained creativity has led me to the inevitability of self-awareness, self-development and self-knowledge.

An installation view of Kaili Chun’s Veritas 2012, in ‘ʻAi Pōhaku, Stone Eaters’, curated by Drew Kahuʻāina Broderick, Josh Tengan and Noelle MKY Kahanu, and organised by Puʻuhonua Society, Hōʻikeākea Gallery, Leeward Community College, Waiawa, ʻEwa, Oʻahu, April 2023 / Courtesy: The artist / Photograph: DKB

An installation view of Kaili Chun’s Veritas 2012, in ‘ʻAi Pōhaku, Stone Eaters’, curated by Drew Kahuʻāina Broderick, Josh Tengan and Noelle MKY Kahanu, and organised by Puʻuhonua Society, Hōʻikeākea Gallery, Leeward Community College, Waiawa, ʻEwa, Oʻahu, April 2023 / Courtesy: The artist / Photograph: DKBOver the years, Aunty Manu’s steadiness has created numerous environments for individuals, groups and communities to ʻauamo kuleana (shoulder our responsibilities), practise excellence and transform ourselves collectively in the process. As the current Konohiki (facilitator) for Kūlana o Kapolei, a Hawaiian Place of Learning, at University of Hawaiʻi, West Oʻahu, Aunty Manu continues to work towards more just and sustainable futures for Hawaiʻi, and through Hawaiʻi, for the world — ‘Ea Hawaiʻi, Ea Honua’. Together with Indrajit Kumara Samarasingha Gunasekara, an Indigenous farmer from southern Sri Lanka, she leads NiU NOW!, a community cultural agroforestry movement that deconstructs capitalism and encourages a sharing economy. More specifically, NiU NOW! emerged to affirm the significance of niu (coconut) and uluniu (coconut groves) in ecological systems. At the centre of the movement is the re-establishment of a loving relationship with niu and the ancient practices surrounding this ‘tree of life’. Founded in backyards, in the hearts of its practitioners, and through the cultural practices of their communities, NiU NOW! is not large-scale uluniu for economic gain, but rather uluniu for a healthy society and everyone’s wellbeing.

Manulani Aluli Meyer discusses the centrality of ʻāina (that which sustains) to ea (sovereignty, life, breath, freedom):

You can summarise Hawaiian epistemology in one idea and that’s aloha ʻāina — love of land. And we love the land because of ʻāina aloha, because we know that the land loves us. Our geography shapes our knowing. People who know what that means have spent time in place and have loving relationships with their surroundings. [As it is said,] ‘Hahai nō ka ua i ka ululāʻau’ (‘Plant a forest and the rains will come’). Share purpose with others and transform the world. My purpose is to learn how to love better, to embody aloha in all its fullness. That’s it. What is the purpose you want to share with others?

As a teenager, I would assist Aunty Mele in art workshops and mural projects across Oʻahu. At Ke Kula ʻo Samuel M Kamakau, a Hawaiian charter school in Koʻolaupoko, Aunty Mele helped young people to establish relationships with art, informed by their cultural identities and experiences. There is no easy way to address personal pain and intergenerational trauma, but expressing oneself creatively in a safe and supportive learning environment can be a powerful beginning to a lifelong journey of healing. Since 1992, Aunty Mele’s ‘classrooms’ have taken many forms — a steel-framed, blue tarp tent; a wooden park bench on the beach; a pothole-ridden parking lot; a correctional facility; a family’s backyard; a public library; and the white walls of a state-funded museum. No matter where the learning happens, it is never about the art or the final product; rather, it is about connecting with people and sharing a culturally rooted creative process along the way, as Meleanna Aluli Meyer explains:

As a young, widowed mother of two boys, I was carried, like a high tide, to this place of going ‘DAMN!, there’s just so much trauma, rage and confusion in me’. Finding out all the deplorable things that have happened to Hawaiians over the generations put me on a course of corrective action; as in, get myself educated, so that I can make more informed decisions and then try to better understand the reasons for all of the dysfunction in the Hawaiian community — in the lives of my own family, our cousins and their families. Desperation. Insanity. Addiction. Suicide. Families experience loss and difficulties at some point. But if we can practise forgiveness, patience and kindness throughout it all, then we can do it within our communities and beyond. I work whenever a need presents itself, and I don’t go where I’m not invited. Serving as a community arts educator has been my own lifelong education.

Painting Nā Akua Kiaʻi 2023 for ‘ʻAi Pōhaku, Stone Eaters’, with Kānaka ʻŌiwi artists (l–r) Kahi Ching, Al Kahekiliuila Lagunero, Solomon Robert Nui Enos, Harinani Orme, Carl FK Pao and Meleanna Aluli Meyer at the Screenprinting Studio, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Department of Art and Art History, Mānoa, Kona, Oʻahu, April 2023 / Courtesy: The artists / Photograph: DKB

Painting Nā Akua Kiaʻi 2023 for ‘ʻAi Pōhaku, Stone Eaters’, with Kānaka ʻŌiwi artists (l–r) Kahi Ching, Al Kahekiliuila Lagunero, Solomon Robert Nui Enos, Harinani Orme, Carl FK Pao and Meleanna Aluli Meyer at the Screenprinting Studio, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Department of Art and Art History, Mānoa, Kona, Oʻahu, April 2023 / Courtesy: The artists / Photograph: DKB During an artist-led discussion with Meleanna Aluli Meyer, in front of Hawai‘i Loa Kū Like Kākou 2011 by Meleanna Aluli Meyer, Al Kahekiliuila Lagunero, Harinani Orme, Kahi Ching and Solomon Robert Nui Enos, a mural project organised by Puʻuhonua Society in collaboration with the Office of Hawaiian Affairs and Hawaiʻi Tourism Authority, during ‘Hoʻoulu Lāhui: Regenerating Oceania’, the 13th Festival of Pacific Arts and Culture, Hawaiʻi Convention Center, Waikīkī, Kona, Oʻahu, June 2024 / Courtesy: The artists and Hawaiʻi Convention Center / Photograph: Allyson Ijima

During an artist-led discussion with Meleanna Aluli Meyer, in front of Hawai‘i Loa Kū Like Kākou 2011 by Meleanna Aluli Meyer, Al Kahekiliuila Lagunero, Harinani Orme, Kahi Ching and Solomon Robert Nui Enos, a mural project organised by Puʻuhonua Society in collaboration with the Office of Hawaiian Affairs and Hawaiʻi Tourism Authority, during ‘Hoʻoulu Lāhui: Regenerating Oceania’, the 13th Festival of Pacific Arts and Culture, Hawaiʻi Convention Center, Waikīkī, Kona, Oʻahu, June 2024 / Courtesy: The artists and Hawaiʻi Convention Center / Photograph: Allyson IjimaThe first community mural I worked on with Aunty Mele was in 2004, when I was 16. At the invitation of Noelle MKY Kahanu (Kanaka ʻŌiwi), then Director of Community Affairs, at the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, Aunty Mele developed a large, 40-panel mural that would become part of the renovation of the Hawaiian Hall at Bishop Museum, which opened in 2009. Painted by school students and community members over a period of ten weeks, Hoʻohuli Hou 2005 is a rumination on a wānana (prophecy) attributed to Kapihe, a kāula (seer), and adapted from Hawaiian Antiquities (Mo‘olelo Hawai‘i) (1898) by Kanaka ʻŌiwi historian Davida Malo. The mural celebrates the proverb: ‘E iho ana ʻo luna. E piʻi ana ʻo lalo. E hui ana nā moku. E kū ana ka paia’ (‘That which is above shall be brought low. That which is below shall be lifted up. The islands shall be united. The walls shall stand upright’). Meleanna Aluli Meyer elaborates on the mural’s powerfully enduring tenet:

Our ancestors are extraordinary, and they want the best for us. I believe in them and feel their presence. I am an embodiment of their knowledge and strive to continue their good works. Everyone I vision and paint and heal with, we all channel ancestral memory in our own ways. Together, we hold it, we feel it, we pray for it. Our work helps remind us of what we are supposed to be doing, of what we are, of what we should be caring about. It hasn’t been easy, let me tell you, but it’s certainly been worth the effort. At the end of the day, we only need to remember that Spirit is in all things and as many of my kumu, my beloved teachers, have said to me over the years, ‘It matters not what you practise, but that you practise’. Simple right!?

Following Hoʻohuli Hou 2005, Aunty Mele oversaw many more community murals and formed a hui (working group) with longtime friends and fellow Kānaka ʻŌiwi (Native Hawaiian) painters Al Kahekiliuila Lagunero, Harinani Orme, Kahi Ching, Carl FK Pao and Solomon Robert Nui Enos. Of their collaborative work, two projects stand out — ʻĀina Aloha 2015 and Hawai‘i Loa Kū Like Kākou 2011. ʻĀina Aloha is a two-sided painting addressing generational healing within Native Hawaiian communities. Since 2015, the mural has travelled to local and international conferences that focus on dealing with historical and cultural trauma, and in 2023, it was included in ‘Sharjah Biennial 15: Thinking Historically in the Present’. Hawai‘i Loa Kū Like Kākou is an eight-panel, 64 x 10 feet (19.5 x 3 metres) meditation on ʻauamo kuleana, a Native Hawaiian concept encapsulating the burden and privilege of responsibility in caring for Hawaiʻi and the planet. The mural — which shows another way of being in the world — was produced in advance of the 19th Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Economic Leaders’ Meeting, held in Honolulu in November 2011. It was also a direct response to a lack of Native Hawaiian art at the Hawaiʻi Convention Center, when public art was commissioned for the building by the State of Hawaii in the late 1990s. A testament to the ways in which community murals can raise awareness and bring about meaningful change, Hawaiʻi Loa Kū Like Kākou is now prominently displayed near the building’s entrance.

Manulani Aluli Meyer explains the importance of living in a world where your world view is valued:

Aloha (loving) is the primal energetic force of our collective evolution; it is the genesis of world transformation. You know how I know that? Because others told me it was! I remember listening to kūpuna (community elders), to family and to friends tell me about Hawaiian intelligence, and that, in the end, it just boils down to aloha. And then, suddenly, I felt intelligent. Like, wow! You know, I was made to feel so stupid in this other world, but that wasn’t the one I wanted to inhabit. That was in 1997, while I was pursuing a doctorate in Philosophy of Education at Harvard University, because I wanted to study with Howard Gardner, whose theory of multiple intelligences resonated with me at the time. That’s also when I realised how sick US society really is.

On 13 June 2024, at the end of the 13th Festival of Pacific Arts and Culture, the Hawaiʻi Contemporary Art Summit 2024 opened at the Hawaiʻi Convention Center. As a thematic precursor to ‘Hawaiʻi Triennial 2025: ALOHA NŌ’, the free, multi-day, multi-site event brought together artists, curators and thinkers from Hawaiʻi, the Great Ocean and around the world to consider the triennial theme through a series of talks, film screenings, artist presentations and workshops.11 Amid the converging arts and cultural scenes of Moananui, Aunty Manu delivered a keynote, ‘ALOHA NŌ: Hawaiʻi’s Role in a Worldwide Awakening’, inspired by the teachings of respected Kānaka ʻŌiwi elders and cultural knowledge holders Aunty Pilahi Paki, Aunty Edith Kanakaʻole, Aunty Lynette Kahekili Paglinawan and Aunty Pūlama Collier. During the session, she spoke movingly to notions of aloha as a practice that flows through truth-telling, healing, spirituality and the Hawaiian sovereignty movement, during this time of radical transformation on a global scale.

Later in the day, Aunty Mele participated in a roundtable discussion, ‘Pewa: Healing and Truth Speaking’, with fellow Triennial artists Megan Cope (Quandamooka people), Carl FK Pao and Emily Mafileʻo (Tongan people) of Taro Patch Creative, which was moderated by curator Mina Elison (Kanaka ʻŌiwi). The group engaged in conversation about loss and grief in a postcolonial and capitalist context, as well as different modalities of healing and connectivity through artistic practices that mend cracks or divides in communities. Across the three days of Art Summit 2024, my mother Maile, a board member of Hawaiʻi Contemporary, actively strengthened relationships between artists, audience members and community partners, in seen and unseen ways as she has done diligently since the organisation’s inception over a decade ago. Maile Meyer on her uplifting approach to community:

Everything we do, it’s all about lifting up the work of Native Hawaiian, Hawaiʻi and Pacific creatives. If we can just meet people where they are at and help to support them, so they can continue in the direction they want to go — that’s it right there, that’s enough. And so it’s always about nurturing relationships through community, in all the ways we can. This is how we rise, through a different understanding of exchange.

Witnessing my mother, aunties and their extended support networks of artists, friends and frequent collaborators over the course of my life has instilled in me a deep appreciation for all those who care, individually and collectively, for the practices and places that sustain us. My family taught me that meaningful change happens when we work together and take action, each in our own way — and for that I am forever grateful. As Native Hawaiian and local creative communities of Hawaiʻi continue to navigate various international art worlds, may we always share our family stories of art, culture, education and healing for they remind us where we come from, who we are and what we might be, especially if we embody aloha ʻāina — love for lands, waters and skies.12